The brief.

In this second intellectual production, we need to select and research a tool, situating it within actor-network theory. The following work explores the filmstrip, its context, what came before it and what came after. The work is presented as a 5-slide deck exploring the use of the filmstrip as a learning tool. Each slide is situated sequentially below (just like a filmstrip) with speaker’s notes below (like a filmstrip’s accompanying instructional text!)

This is its table of contents:

McLuhan’s Tetrad and the filmstrip.

Actor-network theory (Latour, Latour, Latour).

A bit more Latour. How does the filmstrip impact us? What do we delegate to it and what does it prescribe back to us?

Filmstrips, object, things, facts, and concerns (plus a little representation).

ANT and ME compared (I’m prepared to be very wrong here).

Slide notes:

To begin this presentation, we will take Marshall McLuhan’s tetrad and apply it to the filmstrip, a now-obsolete audio-visual tool often used in training and education environments (St-Pierre, 2021). In McLuhan’s tetrad, a medium undergoes four processes in its lifespan. It first extends or amplifies a process or human ability, which is often a quality retrieved from the past (McLuhan, 1977; Memarovic, 2016). In possessing novel affordances, it then obsolesces other media but, once its pushed as far as it can go, it becomes a new medium, or reverses into a medium with opposing properties (McLuhan, 1977; Memarivic, 2016).

The filmstrip is a primarily visual tool that portrays visual representations of educational topics by situating images in a linear narrative shown through a manually operated projector. The filmstrip went through several iterations in presentation and packaging, complicating the analysis a bit. It began as a simple sequence of still photographs and over time became a more comprehensive media kit with accompanying audio on record or cassette with textual instructions acting as teachers’ guides (St-Pierre, 2021; Teaching Aids News, 1963). Later, they were also included in so-called multi-media kits including photographs, films, and slides (St-Pierre, 2021).

The filmstrip extended the teacher’s ability to represent information visually, to illustrate concepts, or to demonstrate processes, historical events, and generally to bring textual information to life for learners. The tool retrieved past visual aids like the magic lantern, which used glass slides and (originally) oil lamps to project still photographs into flat surfaces (Edelson, 2012). It also recalls the smaller, personal devices for viewing visual media such as phenakistoscopes though the filmstrip did not create an animated effect. The filmstrip obsolesced physical media like drawings, charts, or paper maps (though not completely). It eventually reversed into modern film media with the advent of the VCR, which seemed a natural evolution given the accompanying audio and texts filmstrips were eventually sold with (St-Pierre, 2021).

Note:

I am in agreement with Levinson that the reversal stage requires clarification. It is not clear to me if the reversal means the technology is obsolesced by morphing into a different medium as above, or if it means that by being pushed to oppose itself, it retrieves something. I used VCRs and motion picture film to describe this reversal as an intensification of the obsolescence here, but what if the filmstrip reversed into early digital slides like Apple Macintosh’s Presenter as a retrieval of the obsolesced (and is that a good example…)?

Image credit: "The evolutionary filmstrip" by Scott McLeod is licensed under CC BY 2.0. To view a copy of this license, visit https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/?ref=openverse.

Slide notes:

After establishing some of the elements of McLuhan’s tetrad, we’ll move into thinking about Actor-Network Theory (ANT). Latour (1996), clarifies the two main components that make up the theory - self-evidently the network and the actor. Networks often bring to mind technological networks like computer networks that have compulsory paths that inform the circulation of information between strategically connected nodes that might be very distantly related (Latour, 1996). However, networks in ANT can be local networks made of any possible connection. The paths within this network are not compulsory, but can freely associate with any actor in ways that are not required to be strategic. In this way, the network avoids hierarchies between actors (Latour, 1996).

Two other unique aspects of the theory include the inclusion of actors in the network and how they are analyzed. If hierarchies are successfully avoided, then any actant can be an important part of the network regardless of its status as human, non-human, or hybrid (Latour, 1996). The actant can be described in full by noticing all of its relevant associations. The resulting collection of connections can then be analyzed for explanations without ever having to leave the network to determine causality. Inferences are made by extending the connections between actors as far as they can be taken (Latour, 1996).

Slide notes:

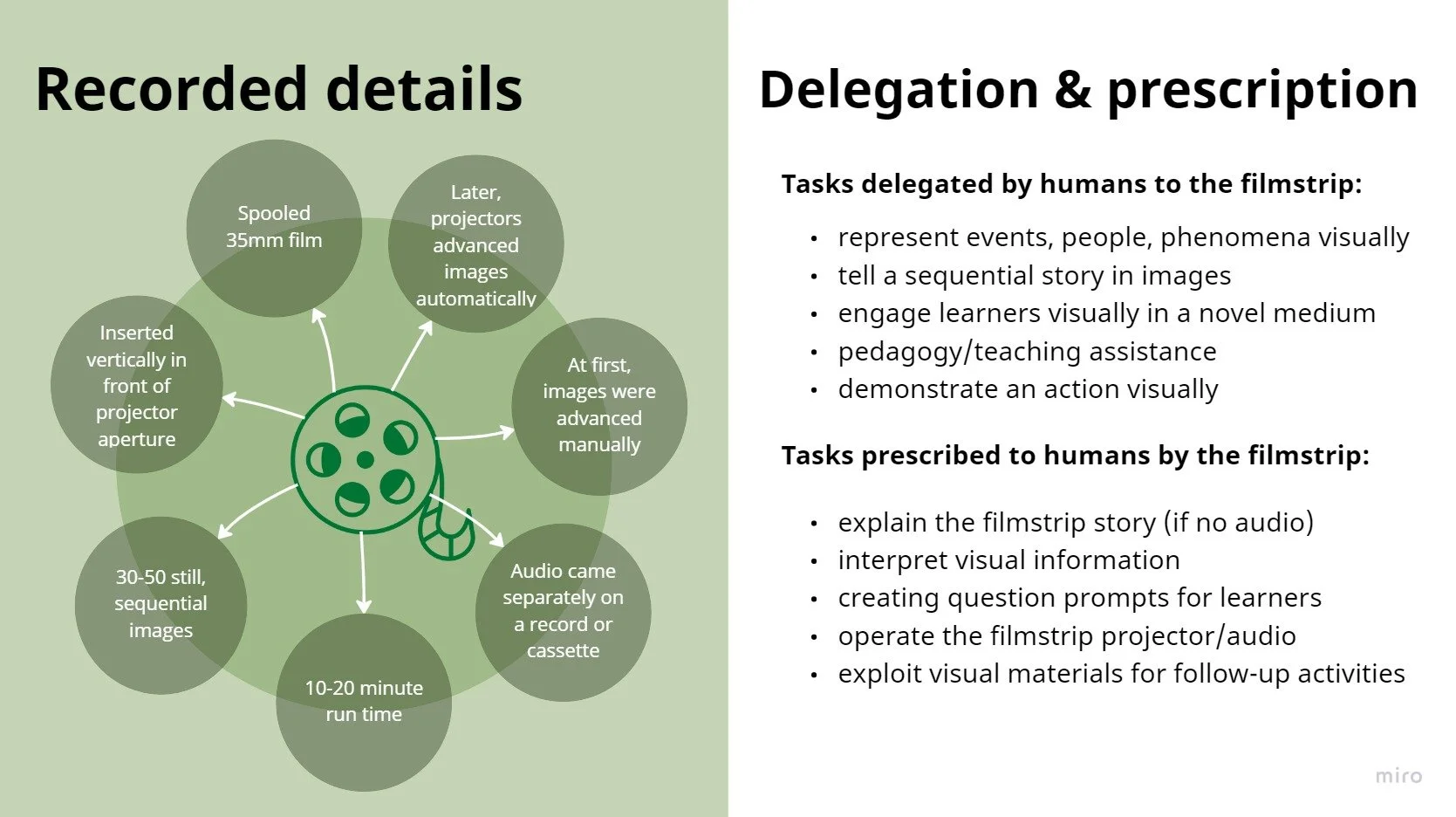

Our next step is to take Actor-Network Theory and apply it to our filmstrip tool. Latour (1992) describes the ways in which a door functions, elucidating all of its relevant details, and the tasks that humans have delegated to it. In the process of delegating tasks to non-humans, the non-humans prescribe tasks back onto human actors (Johnson, 1998). In our description of the details of the filmstrip, we can see that it was made up of a spool of 35m film with 30-50 still, sequential images included. The run time of the media was around 10-20 minutes if the teacher kept to the pacing in the teachers’ guide, or used accompanying audio that cued the time to advance the image. This reflects Latour’s description of the door in that there were later advances in the technology that delegated more tasks onto the non-human. The first iteration of the filmstrip required teachers to narrate a story, or interpret the visual information for learners. Later versions removed that decision-making and placed it onto the whole multimedia kit that surrounded the filmstrip including its audio, pacing, and accompanying activities from the guide.

In terms of delegation and prescription of tasks, we have crafted a set of imperative sentences perhaps silently uttered by the filmstrip for our benefit (Johnson, 1988). We have included a list that considers all stages of filmstrip evolution. At its most basic, teachers expected the filmstrip to tell a visual story and represent information visually. The images engaged learners of all sorts, but were especially beneficial for those whose educational journeys were non-traditional, such as those with lower literacy levels or learning difficulties (Dimmick, 2020). Later versions delegated teaching strategies to the machine, from simple timing/pacing to narrative and pedagogy. The machine prescribed teachers quite a few tasks in early versions including interpreting and explaining the images, especially their context in the sequence. Teachers might have also had to exploit the materials and mine them for follow-up activities and question prompts to generate conversation about what learners were seeing. At their most advanced, teacher had to simply operate the projector, though even that was delegated to the machine in the latest versions of filmstrip projectors.

Slide notes:

In the previous explanation of the filmstrip and actor-network theory, it was evident how important both the network, and the actors are to the theory. It is also evident that Latour aims to complicate things - both in reinterpreting things quite literally, but also in analyzing the fibrous connections between things in the network rather than the things themselves. In a conversation between Serres and Latour (1995), they describe objects as easily understood to be useful, but that we can never see clearly enough how they create new associations. They refer to the new relations between objects as quasi-objects represented not by nouns but by pronouns and prepositions (Serres & Latour, 1995). Such relational language without which we could not make sense. I wonder if that is another way to think about matters of fact, concern, objects and things. Nouns are clearly defined, discrete, and easily understood. We complicate nouns by making them relational and adding language to configure the nouns - adding the between and within to our syntax.

Where does that leave our filmstrip? Pushing our analysis further from the medium to what is being represented by the medium (the pictures), we might have more to discuss. This is beyond my scope here, but the network associated with the filmstrip doesn’t end at the projector, the teacher, or the actions delegated to or by the teacher/filmstrip. The missing piece is what is associated to the images and moreover, the linear sequence of images represented. The filmstrip is an object. It delivers short bursts of easy-to-digest visual content with ready-made auxiliary materials. To look at it from the perspective of a thing, we’d need to talk about how the images relate to each other, what choices were made in the representation of a topic, who made the images, among many more fibrous connections to do with the complicated nature of distilling something down in order to easily represent it.

Speaker’s notes:

In comparing McLuhan’s media ecology with Latour’s actor-network theory, a key similarity appears to be the idea of objects as belonging to networks and associated with other objects. McLuhan describes this in his ideas of figure and ground. Perceptually, we are caught first by the figure, while the ground fades away. The figure is in focus, shaped by the background - without it there is no figure (in the arts we call this the difference between positive and negative space). McLuhan describes the figure as the content, while the ground is the environment, context, or medium (Stalder, 1998). For Latour, the associations and connections in the network are what make up the environment within which actors and actants exist. However, while an environment and network are important for both theories, they are conceived of differently.

ANT conceives of networks not as whole environments, but as sets of associations that translate information (Latour, 1996). The focus (figure) might be on how each association relates to each other rather than only on the medium. The times at which the translations occur is also different. McLuhan perceived of his tetrad as stages in a process, though as Levinson (1977) points out, he does not specify a time for them to take place and so his model loses predictive ability (it would be very useful to know for example, when a medium has been pushed too far and will reverse). Latour’s ANT appears to be conceptualized as a continuously dynamic network and makes no claim about when translations between associations begin or end.

Finally, it seems the way media take a form are very different between the two theories, maybe in relation to how we think of the actors included. For McLuhan, though the reading was not exhaustive, the theory does not look hard at actors. Rather, the context shapes the actors, as if humans lose agency to media by allowing it to shape what we do. Latour on the other hand, invests more time in thinking about human/non-humans/and quasi-humans and suggests that it’s the complex associations between each of them that translates the actions they take and evolves them into new actions (Feldman, 2022). By analyzing the relationships we find explanations within the network (Latour, 1996).

Image credit: Photo by Stanisław Gregor on Unsplash

Some fun bits (I read a lot).

-

“A new filmstrip set entitled TEACHING READING WITH GAMES has been released by Bailey Films, Inc. 6509 De Longpre Avenue, Hollywood 28, California. The set includes one 61-frame color filmstrip, one 12" long-playing record, one 16- page illustrated manual, and a fibre storage-shipping case.

Produced by instructors at Los Angeles State College, the set is designed to help the class- room teacher provide individual reading practice for students in a way that is purposeful, enjoyable, and motivational. The complete filmstrip kit is priced at $17.50.”

Teaching Aids News, 1963

-

“NEW S VE FILMSTRIPS EXPLORE THE COMMUNIST CHALLENGE

"Communism: A Challenge to Freedom" is the subject of a new set of color sound filmstrips released by the Society for Visual Education, Inc., 1345 Diversey Parkway, Chicago 14, Illinois.

Classes in American or World History, Economics, Civics or Current World Problems may find this series useful. It is also recommended for use by church, social, PTA, civic, service organizations, Scout meetings, and veterans groups.

"Communism: A Challenge to Freedom, Group I" contains four film- strips with 33-1/3 rpm records: What Is Communism?, Communism and Government, Communism and Economics, and Communism and Human Rights. The second part of the series, "Communism: A Challenge to Freedom, Group II," discusses the history of Communism, the Cold War, the Communist Party and the American in the Cold War. Group I is available for immediate shipment; Group II, now in preparation, will be ready in February, 1964.

Produced in cooperation with the Institute for American Strategy, Chicago, Illinois, the series was written by William F. Keefe, former Press Officer, U.S. Information Agency in Europe, and illustrated by Robert S. Robison, head of the Department of Design and Illustration, Washington University, St. Louis, Missouri.

Each filmstrip, in color, with narration on accompanying long-playing record, sells for $11.00. Each group of four filmstrips, two records (with narration back-to-back) and teacher's guides, is $31.00. The complete set of eight filmstrips, four records and teacher's guides will be priced at $50.50.”

Teaching Aid News, 1963

-

Toby Zieggler and Elizabeth Johnson, extract from The Alienation of Objects (London: Zabludowcz Collection, 2010) 57.

“He develops a disregard for the objects around him - Silly lamp for believing it is on the countertop. Ridiculous chair for concurring to hold me up. Lamp and chair stare back at him blankly. He forgets, he agreed to all this, he gave consent for each second to murder the last.”

References.

Dimmick, M. (2020). Maria Varela's Flickering Light: Literacy, filmstrips, and the work of adult literacy education in the civil rights movement. Community Literacy Journal, 14(2), 49-71.

Edelson, J. (2012, September 2). Filmstrips and Education. Retro Educational Technology. https://www.retroedtech.com/2012/09/filmstrips-and-education_2.html

Johnson, J. (1988). Mixing humans and nonhumans together: The sociology of a door closer*. Social Problems, 35(3), 298-310.

Latour, B. (1992). Where are the missing masses? The sociology of a few mundane artifacts. In Bijker, W. E. and Law, J. (Eds.), Shaping Technology/Building Society: Studies in Sociotechnical Change (pp. 225-258). MIT Press.

Latour, B. (1996). On actor-network theory: A few clarifications. Soziale Welt, 47, 369-38.

Levinson, P. (1977). Preface to Marshall McLuhan’s ‘Laws of the Media'. et cetera, 34(2), 173-174.

McLuhan, M. (1977). Laws of the media. et cetera, 34(2), 175-178.

Memarovic, N. (2016). Community is the message: Viewing networked public displays through McLuhan’s media theory. In: Dalton, N., Schnädelbach, H., Wiberg, M., Varoudis, T. (Eds.), Architecture and interaction (pp. 162-185). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-30028-3_8

Serres, M. & Latour, B. (1995). Where things enter into collective society. In A. Hudek (Ed.), The Object: Documents of Contemporary Art (pp. 37-39. Whitechapel Gallery (London), MIT Press.

Stalder, F. (1998, October 23-25). From figure / ground to actor-networks: McLuhan and Latour [Conference paper]. Many Dimensions: The Extensions of Marshall McLuhan Conference, Toronto, ON. http://felix.openflows.com/html/mcluhan_latour.html

St-Pierre, M. (2021, September 22). Back to the future, or a short history of the filmstrip: Curator’s perspective. NFB Blog. https://blog.nfb.ca/blog/2021/09/22/back-to-the-future-or-a-short-history-of-the-filmstrip-curators-perspective/#:~:text=The%20filmstrip%20was%20essentially%20a,the%20teacher%20could%20read%20aloud

Teacher Education Filmstrip. (1963). Teaching Aids News, 3(11), 16.

Veldman, F. (2022). Into Latour. Parliament of things. https://theparliamentofthings.org/parliament-parlement-van-de-dingen-noordzee-ambassade-bruno-latour/